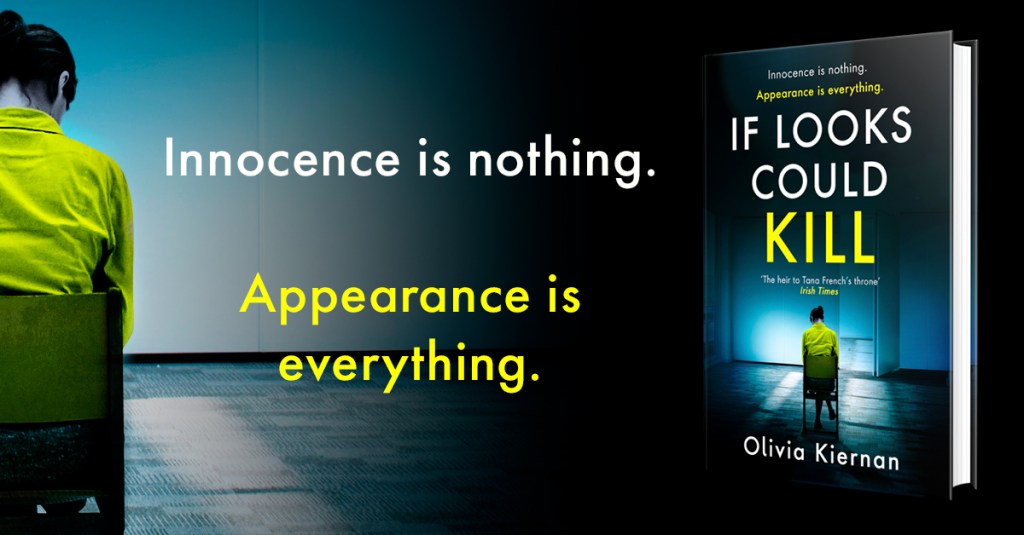

Read the first chapter of If Looks Could Kill

Olivia Kiernan’s acclaimed Frankie Sheehan crime series is back for the third installment, If Looks Could Kill. She’s got a missing person to find, and is about to discover that some families are built on dangerous deceptions, with ultimately murderous consequences. Start reading the first chapter below, and you can read more about the book and order your copy here.

You’ll find the Gardens buried in the heart of Dublin, away from the grey Liffey waters and the stiff smile of the Ha’penny Bridge, on down, beyond Grafton Street’s red-brick road and the old ghosts of Trinity College. Somewhere around a corner, up a narrow street, is the entrance, framed with concrete pillars set into an old stone wall. Inside, winged angels stand watch over dark pools and sunken lawns. The trees form hidden avenues, follow-me trails that lead to fountains, tumbling waterfalls and neat box-hedge mazes. The rusted iron arm of a sundial observes time here and, on this day, it is casting its shadow to one o’clock. The late February sun is a scream of cool light in the sky and slowly the park, whose waiting trees are full of bright new foliage, begins to fill.

First, a couple of teenagers: a boy dressed in loose jeans and a school shirt, his sweater tied low on his hips, his arm around a girl. She’s maybe fourteen, thin and small, her school blazer is over one arm, her skirt rolled up at the waist comes to midthigh.

Thick black tights cover her legs, a pair of black slip-ons on her feet, the backs folded under her heels.

She bumps along next to the boy, her head forced a little forward by the weight of his arm. They make their way towards one of the fountains, where the boy’s arm drops away and they both take the time to shuffle free of their schoolbags. The boy sits on the fountain’s edge, the girl next to him. She has to lift herself up onto the stone and when she sits, only the tips of

her toes skim the ground. She looks up at the boy and he looks down at her. Then they are kissing, at first only faces turned to one another, but after a few moments, the boy’s hand goes to the girl’s and she turns more fully to him.

In this time, a woman enters the park, a toddler in hand. The toddler, despite the brightness of the day and the slow climb of the temperature, is wearing a thick padded coat, a scarf and round fluffy earmuffs. They walk down one of the little paths, then the toddler breaks free, wellied feet pumping towards one of the benches that looks out on the lawn. She throws herself at it, using her padded middle to lever herself onto the seat. The woman joins her and promptly reaches into a bag to remove a blanket, which she spreads on the bench between them. She passes a juice box to the toddler then arranges the rest of the bag’s contents of Tupperware on the blanket. The toddler brings the juice to her lips, her legs kick a beat beneath her and the woman unwraps a sandwich and sits back, her face tipped to take in the most of the sun’s warmth.

It’s filling up now. Not packed, but enough of a sprinkling of visitors to signal lunch hour. A young woman carries a takeaway coffee to a favourite spot to read a book. A group of suits cradling paper lunch-bags, energy drinks and crisps pass her.

The woman watches the men settle around a bench on the opposite side of the park. They’re loud with banter carried out of the office. Something, a shared joke perhaps, sets one of them off and there’s a roar of laughter. The sound makes the kissing teens look up.

It is around this moment that Rory McGrane stops briefly outside the park gates. Pedestrians, racing against the thin slice of their lunch hour, bump up against him as they move by, on to cafés, corner shops or pubs to meet friends, lovers or escape work colleagues. Rory steps a little to the side to let a group of people pass. He takes a moment to watch them, observing their walks, the ease of their movements: relaxed, hands in pockets, the occasional pat of a back or shoulder, the friendly squeeze of a forearm.

Rory’s hot, but he barely notices. In an unconscious movement, he lifts a hand to his throat and runs a strong finger around the neck of his shirt. He took his time ironing the shirt this morning. Pressing creases along the arms like he’d been taught to do. In his other hand, he feels the weight of his navy holdall. He tightens his grip around it then turns into the park, away from the manic din of the traffic and the quiet tinkle of the Luas as it snakes through Dublin city.

The park is not as busy as he thought it would be, but it will be enough, he thinks. It has to be because he’s not sure he’ll be able to face another attempt. But what choice would he have? None, he thinks. He walks down the pavement; last year’s leaves cling in dry brown clumps to the borders, but there’s fresh growth all around and above him. It’s a good day, not raining, and he’s glad about that if nothing else.

He walks across the lawn and looks around. A little way off, a young woman looks up from her reading. Her coat is spread out on the grass to protect her work clothes. She takes a sip from a takeaway cup then returns to her book, but he can see her focus has been thrown and every now and then she looks in his direction as if waiting for him to make his move.

He can feel the heat coming over him now. The sweat gathering down his back. His mouth turned dry. He puts down the bag then straightens, wiping the back of his hand across his lips and swallowing. He’s surprised at the emotion he’s feeling. Fear.

He had thought once he was here he would feel relieved, almost free, and he experiences a jolt of disappointment that he’s still stalked by his weaknesses.

There’s a young couple holding hands at the fountain. He spies the boy’s thumb moving over and back on the girl’s wrist, sees the soft smile creeping across the girl’s face. And he thinks what it might feel like to be young once more. To have his chance again. Avoid the mistakes. He swallows again. Focuses. There is only forward. That is all that’s left to him.

He squats down and opens the zip of his bag. He pushes his documents aside until he finds the small triangular case. He unclips it and removes his gun. It’s been some time since he’s had to use it but he won’t need much skill to do what he needs to today. When he straightens again, he takes another look around.

Too late he notices the toddler on the bench, the mother with her face tipped back in the sun. He hadn’t thought about children.

The woman with the book is watching him again and he sees her eyes drop to the weapon in his hand. Her mouth makes an ‘O’ shape and she scrambles to her feet, knocking the cup into the grass, her book pressed to her chest but she doesn’t run and he wonders at her hesitation. He lifts the gun, his finger suddenly steady on the trigger. A light breeze trembles over his face and he thinks he probably should have shaved this morning, then he places the gun to his temple and pulls the trigger.