Scene of the Crime – Dr Richard Taylor, author of THE MIND OF A MURDERER

Dr Richard Taylor explains where he wrote THE MIND OF A MURDERER, his gripping and eye-opening book which gives insight into life as a forensic psychiatrist.

On a stormy November in rural Dorset I tried my best to describe an equally bleak December some sixteen years previously – but the similarity of those two evenings ended with the weather report. I had been writing the first case history in by book, a case from 2002 which involved dismembered body parts, bin liners and Camden council wheelie bins, and in writing it I realised that the only effective place to write would be back in the city.

While writing an entire book alongside my full-time job in forensic psychiatry I would snatch minutes whenever I could in cafes and restaurants, or even on trains and planes, such as the plane that I took from London City airport to Berlin Tegel for the annual meeting of the Public Figure Threat Assessment Network.

But, mostly, I had to pack in my writing over the weekends. I started off at home, but the short journey from coffee in bed to soft leather chair and unstable corner desk was insufficient to clear my head. So, escaping the distraction of the overflowing recycling bin I would take my heavy 2014 Macbook Pro to Gail’s café in Exmouth market or Grangers in Clerkenwell for breakfast and a morning hunched over the screen. Fuelled by scrambled eggs, I seemed to avoid writers block. The brain fog and procrastination that would usually hamper my legal report writing was replaced by the urgency of my unrealistic deadline and the impatience of my murder victims – straining to get their stories onto the page and out of my head after years of unconscious processing. Once, engrossed in a re-write of a case involving a breadknife straight into the heart of an abuser, I had ignored the low battery warning. Snapping back to the present after the inevitable black screen shutdown I had lost two hours work. From then on I would both save and email myself hourly drafts. But one morning, as the café filled up and my green tea went cold, I realised that the background noise was too distracting. I had to find somewhere silent.

Two weeks of summer annual leave was looming with a chance to write all day. I plumped for the shady interior of the British Library and renewed my long expired reader’s pass. For two weeks I exchanged sunny August days for the cold natural light and air conditioned calm of the humanities reading room, taking only the security approved clear plastic bag for my charger, mouse and Persian rug mouse-mat – a replica of the carpet on Sigmund’s couch from the Freud museum in Mansfield Road.

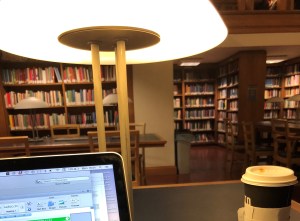

But the British library closes at six so I needed somewhere with longer hours. I discovered that, as an alumnus, I was entitled to a library pass at UCL. Even better it was open 24 hours a day during the week. As a medical student in the 1980s my pre-exam cramming stints had been in the cavernous clinical sciences library on the corner of Gower and University Street but after 90 years service, that had been closed in 1999 and turned into a student common room.

So, I opted instead for the Humanities, Law and languages library along the upper floors of UCLs neo-Grecian central portico. The spiral staircase leading to the Flaxman sculptures fosters lofty academic pretensions and having found my ideal writers hideaway I worked my way along the corridor trying out the separate book-lined reading rooms. First I tried the law library – desks too narrow and acoustics too distracting. Then the fine art library – too dark – and Italian literature – too claustrophobic.

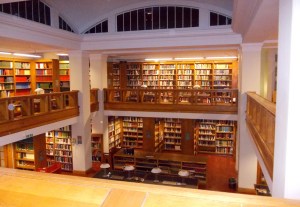

But to the north and up a set of creaking stairs is the Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Modern Icelandic and Old Norse collection, a little known double-level Tardis with deep leather-topped desks, translucent shaded lamps and natural light from the ceiling lantern. Any muffled whispers are absorbed by the Norse and Faorese tomes in a room that is only for assiduous and mostly silent students.

But I wasn’t the only one to have found this tranquil attic. So I started arriving early to bag the desk next to the window on the north side – my favoured spot for early weekend starts and post work nights. By the end of six months I must surely have spent more time amongst the stacks than I ever had during six years of medical and anthropology studies.

One lunchtime, as I was slipping out to the overpriced Sodexho refectory, I bumped into the shelf of books behind my chair and knocked a volume off it and onto the floor. Bending down to pick it up I realised that I had chanced upon the perfect spot for my true crime dissertation – the Stieg Larrson in the original Swedish.